- Home

- Rachel Khong

Goodbye, Vitamin Page 3

Goodbye, Vitamin Read online

Page 3

I roll my window down. “Need a lift?”

“Nope,” Linus says, not skipping any beat. “No thanks.”

“You’re going to leave me all alone,” I say, “down there? With those people?”

He takes a good long look at his mail.

Ten years ago—Linus was a junior in high school, and I was away at college—our father took up with another professor at the school. She taught physics. It had gone on for six months when our mother found out—they were never very scrupulous—after which there were apologies and there was counseling. The professor moved away, and that was the end of that.

My parents never broached the subject with me. Over the phone, they kept conversation light. It was Linus who relayed the goings-on—how strained their relationship had become, how miserable my mother seemed, how helpless. He chose her side easily. The whole thing caught me by surprise—still surprises me.

Anyway, the point is: Linus sees things differently.

Inside his apartment, on his couch, sit neat towers of clean, folded laundry; Linus moves them.

His girlfriend, Rita, is a flight attendant. She’s often gone, and isn’t home now, either.

“Alaska,” Linus says, without my asking. Also without my asking, he hands me a beer and deftly fashions a trail mix out of little airplane pretzel and peanut packets. He empties them into a bowl.

He makes the bed for me with a flat sheet and airplane pillows; he brings me a blanket. He opens the medicine cabinet, where there are sample sticks of deodorant and spare toothbrushes and flat, dehydrated sponges for taking on trips: the sponges save luggage space. They expand on contact with water. He says I’m welcome to use anything, which moves me.

“How is he?” Linus says, finally. This is after three beers. He’s put his library DVD of One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest on TV. He asks the question while juggling the socks he’s rolled into balls. I know it’s a hard question for Linus to ask. The socks mean he can’t ask me straight. I want to dignify it with a response befitting the courage he’s mustered, but all I can manage is, “He’s fine.” Linus knows what I mean: that he’s his stubborn self—unwilling to accept help.

After the movie ends, we change the channels. On one, a woman has buried herself beneath her belongings. All around her there are cartons of expired things she can’t bear to throw away, and a flattened cat.

“Can’t you come home?” I say finally.

“I’ve been home,” is what he says.

And we let the silence hang there between us—not uncomfortably. He refills the pretzel-and-peanut bowl.

At some point we fall asleep, the both of us, children nestled among the laundry.

January 7

Linus makes us thermoses of coffee in the morning and we take them to the beach, where the sky is gray and the ocean is gray and it feels like being wrapped in a newspaper. Seagulls are squawking; the gutsy ones come close and give us piercing stares. They look like Jack Nicholson.

“He’s our dad, though,” I say.

“And I don’t give a shit,” he says.

He sends me off with peanut packets. I get on the I-5 and keep the window mostly rolled down and try to breathe deeply, like Grooms always says I should. But all I can smell is hamburgers, or cows on their way to becoming hamburgers. America.

My car is completely flush with belongings. I can’t see anything in the rearview mirror and this is causing some distress. I cut west, to the 101.

I pull over often. I buy a bag of oranges from a man under a rainbow umbrella. I buy lemons from another man a few miles down. I pocket some rocks at Moonstone Beach, and a couple there asks, in French accents, if I have a steady hand. After I tell them, “Not really,” they hand me their camera anyway.

A truck is carrying a wind turbine that looks immense, like a whale.

Another truck, all black, says eat more endive. It pulls over to let me pass, and the trucker gives me a small wave as I do.

At a rest-stop gift shop, I buy a pencil topped with an eraser shaped like an orange and ask the employee how California came to be known as the Golden State. Was it because of the gold rush, or because of the sunshine, or because of the oranges?

“I’ll have to ask my manager,” the employee says, hurrying off. I don’t stay to learn the answer.

I pull over to get a coffee at a Chevron in San Luis Obispo. The endive truck is parked there, and the trucker is outside, sitting on the curb, eating a waxed paper–wrapped apple pie. He has wavy gray hair and is wearing a Harley-Davidson shirt.

After taking a sip, I cough the coffee onto the sidewalk. My standards for coffee I consider the lowest of low. Meaning this stuff is impossible.

“I meant to warn you about that,” he says, finishing the pie.

He tosses me a tiny bottle containing, it says, five hours of energy and an astonishing amount of B vitamins. He says the feeling you got from it was like the sun coming up in your head.

“That sounds nice,” I say.

“Nice,” he says, “is the goal.”

I used to have scruples about accepting drinks from strangers. Not so much anymore. I take a seat on the curb next to him.

“They’re a trippy little veggie,” he says, about endives. “You grow them in the dark.” He pronounces endives “ON-DEEV.”

There is a couple also outside the Chevron, standing by the trash can: the woman is voluptuous and the man is ruler thin and they are in their forties or early fifties. They talk quietly together. He is leaning into her, and only their stomachs are touching.

“Vegetable jokes,” he says. “It’s all I’m good for anymore.”

“What do you mean?” I say.

He points to the couple. “Isn’t it romaine-tic?”

He takes my empty energy bottle in his hand, which is holding his own empty bottle. It reminds me of church with Joel and his family at Christmas; how, after communion, Joel would take the little plastic cup that had contained the blood of Christ, and stack my cup with his. His hand would brush mine when he did, and I would feel like I was in on something.

When the trucker gets up to throw our small bottles away, I notice, for the first time, the back of his shirt, which says, “If you can read this, the bitch fell off.”

“I like to ride a bike,” he says, when he turns around and sees that I’ve glimpsed the print on his shirt. “What do you do?”

“Sonography,” I say. “Ultrasounds.”

“How is it, working with the whales?” people tend to ask.

“Sonography,” I usually have to repeat. “Not sonar.”

“Are they really as friendly as everybody says?” they’ll continue.

I started reading about echolocation so I could field the questions. The answer to “Are whales friendly?” is “Most are.” The “melon,” which is what you call the fatty organ in the whale head, serves an important function in echolocation.

But the trucker only says, “Good.”

He reminds me of my father. They could be the same age. He sticks his cigarette in his mouth and puffs while he engages both hands to rummage in the inner pockets of his jacket. He hands me a small paper booklet. On the cover of the booklet is a photograph of him, looking somber, and beneath it: COOKERY BY CARL. I open the book. It’s recipes. The first is for endive boats.

“Someone told me it’s a tradition they have in Thailand,” he says. “Over there the thing to do before you die is compose a cookbook. That way, all the guests at your funeral get to depart with a party favor. Somewhere along the line you can crack this open, see”—he opens the book, at random.

“Say you want to cook trout en papillote for dinner. Well, you’re in luck, because there’s a recipe right here. So you get your trout en papillote and as a bonus you remember your old friend Carl, too.”

“That’s a nice tradition,” I say.

I make a motion to hand the book back to Carl and he pushes it away.

“That one is yours.”

“But here

you are, alive,” I say.

“No sense denying that you and I will one day both be dead.”

He stands up.

“Hopefully me before you,” he says.

He shakes my hand.

“A real pleasure,” he says.

I drive past billboards advertising pistachios, the lowest-fat nut, and Merry Cherry stands, with their painted grinning cherries, until the furrows give way to desert, and the desert gives way to the roller coasters in Valencia, and the mountains before Los Angeles.

Upland is shaded and quiet and, by California standards, old. On a clear day, which is most days of the year, there’s this very blue sky and the San Gabriel Mountains, which includes Mount Baldy, the highest point in Los Angeles County. It’s a picture-perfect postcard picture; it looked, I thought, growing up, exactly like one of those posters you affix to the back of fish tanks.

That’s not exactly the truth. I used to think that every fish tank’s backdrop actually was a photograph of these specific mountains. That other mountains existed didn’t dawn on me until embarrassingly late in the game.

My street smells cold and familiar. All the grapefruits are hanging from trees like ornaments. It feels like there’s a sun going down in my head, and outside it is rising as I pull into town, my five hours of energy coming to a not-unpleasant close. On our street there is a squirrel that’s been hit, not freshly, and now looks like smashed cookies.

“Ruth,” says my mother, there to greet me, in the lit driveway of our pink house. I’d forgotten the exact color. It’s the color of a cut, ripe guava.

“Hi, Mom,” I say.

“My toes are frozen,” she says. “Hard freeze. They won’t be producing any oranges this year.”

January 8

Before she leaves for work in the morning, Mom gives me a lesson in the washer and dryer.

“What you do,” she says, “is kick it like this.” She gives the washer—which she’s loaded—a single firm kick, prompting it to start.

“Some other time,” she says, “I’ll show you the thing about this dryer.”

Apparently, the dryer’s deal is that it tumbles, but never with any heat.

Mom retired last year from the high school; now she substitute-teaches. She’s been filling in for Mr. Byers, a third-grade teacher at my old elementary school. He broke his leg in a skiing accident. He’d taken hallucinogens. When the snow patrol finally found Mr. Byers, it was inside the deep snow angel he’d dug himself into. He was singing “On Top of Old Smokey.”

All day, Dad won’t leave his office. I watch educational TV: about how to make Greek salad and chicken potpie, and how to increase the value of your home by painting an ugly brown table black, because as it turns out, an ugly black table is preferable to an ugly brown one. I read ancient newspapers no one has bothered to recycle about improvements in replacement heart valves, prisoners exonerated by DNA evidence, obituaries of notable people I’ve heard of and others I haven’t. I wonder what Bonnie is up to, so I text her. She texts back a photo of a clump of hair she’s swept into a pile that sort of resembles a turtle.

There is, in the backyard, a pile of lumber, for the patio cover my father has forever intended to build. The bird feeder, hanging from the cherry tree, is empty, to my surprise. When we were little, my mother always kept it filled. It always attracted regulars, like a good pub.

Every so often, I check the backyard, to see if any birds are dining at the feeder.

Every so often, I take bathroom breaks: I remove my top and examine myself shirtless in the mirror. My nipples really do look like his.

I wait and wait for his mood to change, but the birds never come, and the mood never changes.

January 9

He shows me another page from the notebook:

Last week I played you the Beach Boys and today you sang the wrong lyrics. You were singing, “I guess I just wasn’t made for these tides” and when I tried to correct you, you said, “Well, they were the Beach Boys, weren’t they?” You made a very good point.

Today you asked about storms, and their eyes. You asked what it was like, to “see like a storm.” You asked, with great concern, “What do birds do in the rain?”

Actually, I remember that.

“They huddle beneath the leaves,” I remember my father saying. “Their feathers shed the rain. You ever heard of a birdbath?” he’d said, when I seemed unconvinced. “Don’t worry. They don’t mind it.”

What else I remember is that despite my dad’s answer, I didn’t feel very placated. I was worried for them, still. When I questioned him further, he seemed irritated.

It was my mother who helped me build a birdhouse. We built it out of Popsicle sticks. The birds didn’t mind the rain, she assured me, but it was nice to have options.

I detach the empty bird feeder from the bare cherry tree. I collect coins from the carpet and put them in my pocket. Later in the day I wash those pants, forgetting to remove the coins. They come out shiny. I call, “Dad?” and receive no response, though I can hear him in there, shifting.

January 10

I shake the sand that’s collected on the welcome mat and wonder if the saying “To wear out one’s welcome” came about because of the mats. Did somebody visit somebody else so often that the WELCOME actually faded? Then I wonder if everyone who’s ever shaken a mat has wondered this.

I do a load of whites and refill a mug with puffed rice while the clothes spin and stay wet. I fold the white, still damp clothes and eat more cereal and do the darks and listen to the sound of the toilet’s periodic flush. Over the phone, Bonnie complains that Vince has lately been leaving his laundry with her.

“And then expecting me to check his pockets,” she says. “For joints.”

“Remind me how old he is?”

“Twenty-five,” she whispers.

This makes me a terrible person, I know, but it comes as a relief to me that my best friend is in a not-dissimilar boat—the unmarried and careerless boat. Which is more like a canoe.

The unofficial plan had been to never abandon each other. Bonnie grew boobs before I did, but we still wore our first bikinis together. We were at Huntington Beach, wearing big T-shirts over our suits. We were fourteen. Neither of us would take her T-shirt off first.

A man on Rollerblades stopped to say hello. He called us pretty, which was exciting in the moment, but we’d learn, later in life, that men tended to say that when they found your appearance confusing, when they couldn’t tell what you were—when you were half-Armenian in Bonnie’s case, or half-Chinese in mine. The man on Rollerblades bought us each large lemonades. When he handed us the lemonades, we gushed thank you, so excited, never having been recipients of this sort of attention. Then he pulled out a condom from his pocket.

He asked, “Do you know what this is?”

We looked at each other, looked back at him, and nodded.

“Will you show me how to use it?” He grinned.

We abandoned our lemonades. We ran.

When Dad comes to the kitchen to take a banana, he notices the fingernail I’ve drawn on it. He seems to notice me, suddenly, too.

He says, “Ruth.”

I say, “Dad.”

“I’m fine,” he tells me.

“I know,” I assure him.

“I told you I’m fine,” he repeats, annoyed. “Why don’t you go home?”

When Mom gets back later she says, “Howard, don’t be like this,” standing outside my father’s closed office door.

“Irascibility is common,” Dr. Lung had told us. “It is, unfortunately, unpredictable. There might be stretches of confusion, followed by days when he seems nearly back to normal.”

“I’m not hungry, Annie,” comes the reply.

She slips a pizza slice underneath the door, giving me a conspiratorial look as she does. It gets pulled in.

Alone at night in San Francisco, after Joel left me, awake with worry about something or other—like getting diabetes or havin

g an embolism—after it was too late to call Grooms to describe to her my symptoms, I’d hear the building sigh, like it was disappointed. I’d hear my upstairs neighbor, Mr. Deforest, turning over in his bed. And then there were the sirens, the car alarms, the city noises.

Here it is so, so quiet.

January 12

Today a man calls the house and introduces himself as Theo, my father’s teaching assistant. I start to ask if he could please hold, when Theo interrupts and says, actually, it isn’t Howard he wants to talk to—he’s called hoping to talk to me.

He and a few other master’s students want to meet for a class, he tells me. It wouldn’t be a real, for-credit class, but Dad wouldn’t have to know that part. Theo normally took care of the administration, anyway. Everybody else would be in on it: the students wouldn’t get credit, of course, and they were fine with that. It would be a way for my father to continue teaching, stay occupied, keep his mind off, well, losing it.

“We could meet on campus, say, once a week,” Theo says. “Howard would continue teaching as usual. As for the administration—well, there’s no reason Levin or anybody else higher up has to know.”

“Hang on. So you’re suggesting that my dad teach a class”—I’m processing this slowly—“that isn’t real?”

“Except that he won’t know it’s not real.”

“We’d lie to him.”

“It won’t be a legitimate History Department class,” Theo says. “In all other ways, it’ll be a class. He’ll teach; we’ll learn. He wants to be teaching. That’s obvious to anyone.”

“Yeah,” I admit.

“None of this sounds easy for him, and trust me when I say we’d all like to help him out here.”

What’s the harm? is Theo’s argument.

I ask why the students would voluntarily attend a class that offers no credit.

“Because we all care about him,” he says. “Your dad’s a good teacher. And a good friend.”

Which shouldn’t come as a surprise, of course, but does.

To me, his being a good or bad teacher didn’t matter: what I remember are those afternoons Dad was in charge of Bonnie and me—those afternoons he lingered over his work, while we wanted so badly to be elsewhere. One more chapter, he would say, barely registering us, while we found ways to entertain ourselves. We’d harvest sour grass outside and chew on the stems; we played Crazy Eights in the one uncluttered corner of his office while the students stopped by, and discussed incomprehensible-to-us topics. I remember a lot of laughing; I remember wanting to be in on it. I stopped tagging along to campus when I started middle school. That’s when I was allowed—finally, it felt—to stay home to watch Linus.

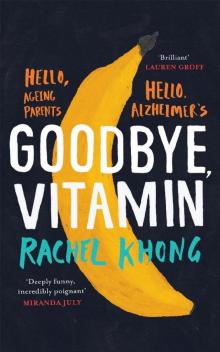

Goodbye, Vitamin

Goodbye, Vitamin